CLEANSING CHAMPARAN AND CHAMBAL OF CRIMINALS: WHEN WILL POLITICS FOLLOW SUIT?: ATUL PRAKASH

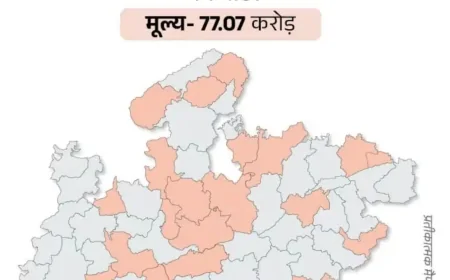

-In a candid conversation yesterday with the esteemed advocate Pramod Kumar Singh, a veteran of Bihar's legal and political battlegrounds, we delved into a pressing question that haunts the corridors of Indian democracy: the stubborn nexus between crime and politics. The topic? The triumphant elimination of dacoits from the lawless ravines of Champaran in Bihar and Chambal in Madhya Pradesh—regions once synonymous with banditry and fear—but the glaring absence of any such purge from the political arena. Singh, with decades of insight into the underbelly of electoral machinations, painted a grim timeline of how this unholy alliance took root and flourished, turning elections into battlefields where muscle often trumps merit.

CLEANSING CHAMPARAN AND CHAMBAL OF CRIMINALS: WHEN WILL POLITICS FOLLOW SUIT?: ATUL PRAKASH

5-NOV-ENG 12

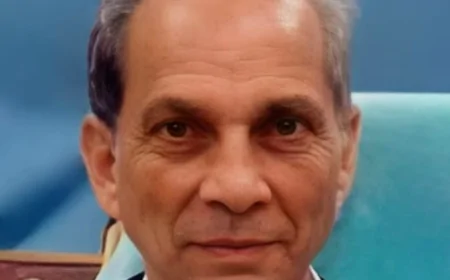

RAJIV NAYAN AGRAWAL

ARA------------------------In a candid conversation yesterday with the esteemed advocate Pramod Kumar Singh, a veteran of Bihar's legal and political battlegrounds, we delved into a pressing question that haunts the corridors of Indian democracy: the stubborn nexus between crime and politics. The topic? The triumphant elimination of dacoits from the lawless ravines of Champaran in Bihar and Chambal in Madhya Pradesh—regions once synonymous with banditry and fear—but the glaring absence of any such purge from the political arena. Singh, with decades of insight into the underbelly of electoral machinations, painted a grim timeline of how this unholy alliance took root and flourished, turning elections into battlefields where muscle often trumps merit.

It all began innocently enough in the 1960s and 1970s, Singh recounted. Politicians, scrambling for an edge in fiercely contested polls, started enlisting the aid of local criminals and goons to intimidate rivals, rig booths, and mobilize reluctant voters. These underworld figures, initially seeking political patronage as a shield against a relentless administration, found fertile ground under the wings of ambitious netas. But the dynamic shifted dramatically by the late 1970s and into the 1980s. Emboldened by their utility, these musclemen began infiltrating the political system themselves—contesting elections, forming alliances, and even ascending to legislative seats. Today, in a stark reversal of roles, no government in Bihar—or indeed much of India—can be formed without the tacit or overt backing of these strongmen. "It's a vicious cycle," Singh lamented. "Criminals protect politicians during campaigns, and politicians shield criminals once in power. The result? A democracy held hostage by fear and firepower."

This isn't hyperbole; it's a documented reality, especially in Bihar, where the scars of "jungle raj" from the 1990s still linger, even as the state hurtles toward its 2025 Assembly elections. To quantify the rot, let's turn to the cold, hard numbers from the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), the watchdog organization that meticulously analyzes candidates' affidavits. Their latest report on the Bihar polls lays bare the extent to which major parties are fielding individuals with serious criminal antecedents—ranging from assault and extortion to more heinous charges like murder and corruption. In a state of 243 constituencies, where over 4,800 candidates are vying for power, the reliance on "tainted" nominees isn't an anomaly; it's the norm.

The ADR data reveals a damning pattern: a staggering proportion of candidates across the spectrum carry the baggage of criminal cases, with "musclemen"—those facing charges related to violent crimes like murder, attempt to murder, or crimes against women—receiving outright tickets from their parties. Here's a breakdown of the key players:

|

Party |

Percentage of Candidates with Criminal Cases |

Number of Musclemen Given Tickets |

|

RJD (Rashtriya Janata Dal) |

76% |

Not specified in report |

|

Congress |

65% |

Not specified in report |

|

JDU (Janata Dal United) |

39% |

7 |

|

BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party) |

65% |

4 |

|

LJP (Lok Janshakti Party) |

54% |

2 |

|

Jan Suraj Party |

44% |

Not specified in report |

|

CPI(ML) (Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist)) |

93% |

Not specified in report |

These figures aren't just statistics; they're a indictment of systemic failure. The RJD, led by Lalu Prasad Yadav's son Tejashwi, tops the list with 76% of its candidates entangled in legal troubles—a legacy of its controversial past that critics say prioritizes caste loyalty over clean governance. The BJP and Congress, both national heavyweights, clock in at 65%, undermining their rhetoric on "zero tolerance" for corruption. Even the CPI(ML), which positions itself as a champion of the proletariat against exploitation, fields 93% candidates with criminal records, raising uncomfortable questions about ideological purity in the face of electoral pragmatism.

The JDU, under Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, fares marginally better at 39%, but the revelation of tickets to seven musclemen shatters any illusion of reform. Nitish's much-touted "Sushasan" (good governance) agenda rings hollow when his party shelters those accused of thuggery. Smaller outfits like the LJP aren't far behind, doling out two such nominations, while the upstart Jan Suraj Party—launched by strategist Prashant Kishor as an anti-establishment force—still sees 44% of its slate burdened by criminal cases, a reminder that even fresh faces struggle against Bihar's entrenched ecosystem.

Why does this persist? Singh attributes it to a toxic brew of weak law enforcement, vote-bank arithmetic, and the sheer lucrativeness of power. In rural Bihar, where booth-level violence can swing entire constituencies, parties view criminal candidates as "assets" rather than liabilities. The Supreme Court's 2003 directive mandating disclosure of criminal records in affidavits was a step forward, but enforcement remains lax. ADR's analysis shows that of the 38% of all candidates with criminal cases this cycle, 17% face serious charges—up from previous elections, signaling a deepening malaise.

The irony is poignant when juxtaposed with historical triumphs like Operation Champaran in the 1970s, where police and vigilantes rooted out dacoits from Bihar's sugar-rich heartland, or the surrender of Chambal's legendary bandits under Vinoba Bhave's Bhoodan movement. Those eras saw society unite against lawlessness, with films like Mera Gaon Mera Desh romanticizing the cleanup. Yet, in politics, the "dacoits" wear suits and file nominations. As Singh put it, "We tamed the ravines, but surrendered the assemblies."

The 2025 Bihar elections, with results due on November 20, offer a litmus test. Voter turnout hovers around 60%, but awareness campaigns by ADR and civil society are pushing for "None of the Above" (NOTA) as a protest option. Prashant Kishor's Jan Suraj, despite its own blemishes, campaigns on "people's power" sans goons, while the NDA alliance (BJP-JDU) touts development over division. The opposition Tejashwi Yadav promises jobs for youth, but his party's stats undermine the pitch.

For Bihar's 130 million residents—many still reeling from migration and unemployment—the question isn't just "when" but "how." Stricter disqualification laws, faster trials for netas, and electoral bonds transparency could help, but it starts with voters rejecting the strongman's shadow. As Singh concluded our chat, "Champaran and Chambal were won by courage; politics demands the same. Until then, democracy remains a hostage."

In the end, eliminating criminals from the ballot might be tougher than from the badlands—but no less essential. Bihar, and India, deserve a politics as clean as its Ganges after a monsoon rain.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0